(Editor’s Note: This was done roughly 2 years ago over the span of many long, extensive phonecalls between Mr. Brummett and Mr. Fanaka. It is one of the deepest pieces I’ve ever read on Fanaka’s films and the motivations behind them–it is also one of the funniest. I am so proud to have this among our list of interviews. Thanks so much Jeff and Jamaa. -DM)

By Jeff Brummett

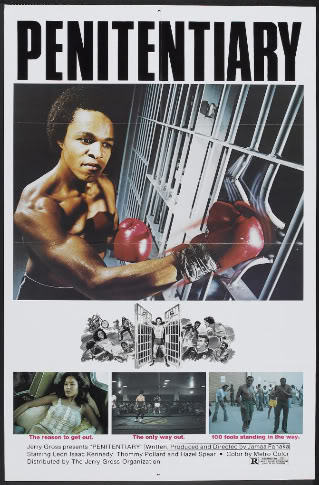

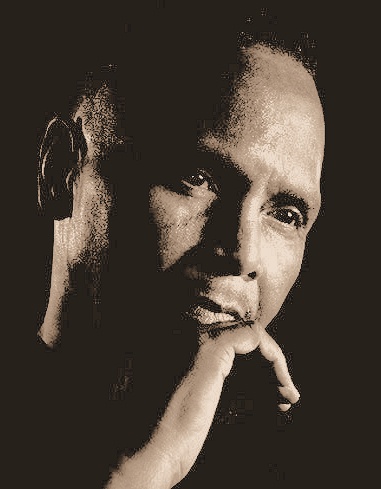

Jamaa Fanaka is a legendary figure in the world of Soul Cinema. A director, writer and producer of several Soul Cinema classics, including the entire Penitentiary series, Emma Mae and the immortal Welcome Home, Brother Charles.

The only student in UCLA history to create a full-length feature out of his senior thesis, Jamaa is a true innovator and pioneer of D.I.Y. ethos who made badass, thought provoking pictures. With Penitentiary as the highest grossing independent movie of 1979, you would think success of that nature would open more doors for Fanaka. Instead he found racism and lack of studio support to be prevalent in Hollywood. In fact he filed a lawsuit against the Directors Guild, charging them with not living up to the quota of minority hiring—just one example of his tenacity for what is right.

He has an unreleased documentary entitled Hip-Hop Hope that he has finished and is working on a script for Penitentiary 4 to be filmed shortly. Still living in Compton, CA, he took time away from his scriptwriting to talk.

Describe how you wound up going to UCLA and how it changed your life.

Well, I’d been in the Air Force for four years and was having trouble looking for a job, there were no jobs. My best friend was a guy named Cash Nelson and when we were in high school, he was too shy to talk to girls, I’d have to do the talking for him, and when I get out of the Air Force, he was now a pimp! He’s got about ten girls in his stable, a Cadillac and everything and I was real impressed by it, you know. But I knew I didn’t want to be a pimp, I loved my family too much.

Now Cash was going to upgrade to a Mercedes, at the time I didn’t even know what a Mercedes was, but I knew I wanted his Cadillac. My other friend and I decided to try to get some money to buy it. Now we knew these lowlife people that were selling drugs, and we figured if we rob them, who they gonna tell? They can’t call the police. So I was planning to rob this drug house with my two friends. They were going to get the gun from my friend’s father, who would be so drunk he wouldn’t know it was gone. Now I’m waiting on Rosencrantz Ave., a real busy street in Compton, when I look over to a storefront window where a sign says “UCLA-You Are Welcome”. That really intrigued me, so I dodge cars to get across the street to get over to the building where there are two lovely interns waiting for me.

Then what happened?

They asked me if I wanted to go to UCLA, and I was thinking, ‘Shit, I’d like to go to the moon too.’ But they helped me with the application and sent for my transcripts and told me how to qualify, I got back and my friend Chucky was laughing at me, saying how this was bullshit, but I thought I had a real chance. So I go back home and wait and sure enough this application comes in the mail, telling me what I got to do, which is take some classes at junior college and maintain a 3.0 average. So I did and graduated with honors and was not only accepted into UCLA, but UCLA film school.

Were you always interested in film?

When I was eleven years old my parents gave me a 8mm camera and I loved that camera, but they forgot to give me film. So I loved playing with the zoom and trying different camera angles and such. So if there was a family event, like a graduation or wedding, they would spring for some film and I would shoot it. After dinner we would watch what I shot and I’d be so happy and that was the first time I remember realizing the power of moving pictures.

So UCLA film school must have been very inspiring.

I was like a kid in a candy shop, they had cameras and soundstages, editing rooms, sound recorders. A four track studio to record music, really everything you need to make a movie. They’d have these assignments called a Project 1 then a Project 2, which were usually five or ten minutes without sound. Now I thought I have all this access to this equipment, I’m going make a feature film.

Is that how Welcome Home, Brother Charles (a.k.a Soul Vengeance) got started?

Absolutely, everyone thought I was crazy to try and do this. A feature film as a Project 2 was unheard of. I was very serious about being a student and felt very blessed and needed to take advantage of this blessing and if I didn’t I wasn’t worthy of it. Now I knew I could make the film I wanted to make without anyone telling me what to do. This project turned into Welcome Home, Brother Charles, which I made as an undergraduate.

Now didn’t you also make Emma Ma (a.k.a. Black Sisters Revenge) and Penitentiary during your tenure at UCLA?

I made Emma Mae in graduate school as my Masters thesis and was getting ready to graduate, but what was I graduating to? No one in Hollywood would return my calls and I had access to all this equipment at UCLA. Plus I had acquired all these grants during my time there and my parents were willing to put their life savings into one of my films. So instead of registering Emma Mae as my thesis, I decided to stay there and do another film, which became Penitentiary. That’s why I am the only person in the history of cinema ever to write, produce, direct and get theatrical distribution for three feature films that were made as part of my curriculum.

Now after the success of Penitentiary did you find it was easy to take the next step with your career?

They always say Hollywood is a liberal town, but it’s actually one of the most conservative, racist towns I’ve encountered. It was much more difficult than when I was in college. There was a stigma that any film directed by a black man would have to be defined as a “blaxploitation” film. The reason why films like The Mack and The Coffy films were called that was they were exploitation films directed by white directors, but starred black actors. I’m not saying that as a negative just as a reality. The term was used as a pejorative term like a putdown, now it’s evolved into its own genre. It has lost a lot of the negative connotations it once had. With older black filmmakers they still remember the negativity that surrounded that. We felt they were using that to destroy black filmmaking and they damn near did. Most of the mainstream population believes that Spike Lee was the first black director and that is obviously not the case. I pitched an idea to Turner Classic Movies about showing some films that were classified as BS…. Before Spike.

Turner Classics aired Penitentiary and Emma Mae; how’d that go down?

That went very well, they picked “Penitentiary” as the movie of the month. My phone and e-mail were blowing up after that. I was contacted by someone from the aquisistion department and she was interested in Emma Mae and Welcome Home, Brother Charles, but Brother Charles didn’t pass their standards and practices. I guess that big dong was a little too much for ‘em. (Interviewers note: The dong Jamaa’s referring to is used in Brother Charles as a weapon for revenge. It is truly one of the most unforgettable scenes ever.)

Can you talk about that scene a little bit?

Obviously it’s meant to be a surrealistic statement showing the ridiculousness of the myth that was created by slave owners to scare white women from having sex with the slaves. They claimed the slaves had penises that tickled their kneecaps, but it backfired on them only intriguing the women more. I really wanted to tackle that myth regarding the size of black man’s sexual equipment and the idea of sexual power. People don’t realize that even though that was many years ago it was still relevant then and if you tell a lie enough times it becomes the truth. Somebody’s got to take a pin and burst that balloon and that’s what I did with Brother Charles, which I still consider the most artistic film I ever made. I still get e-mails and MySpace messages from all around the world praising that film.

I noticed you composed the music for Brother Charles, are you an active musician?

Well actually I wasn’t even a musician then, I play a little conga drums but that’s it. I had the sounds in my mind and when the musicians came in I just made the sounds with my mouth and they would try to play them and eventually wrote them down in note form.

There’s a lot of amazing shots in that film, are you a storyboarding director?

Well, I’m a director who plans, but to be honest I didn’t even know what storyboarding was back then. They didn’t teach that at UCLA. I’m quite an improvisational director actually. I did plan the extreme close-ups, but other shots were on the fly.

I really love the opening sequence of Emma Mae, was that planned in advance or more of an improvisation?

I improvised once I was there, but most of those people in that sequence were already at the park and I just put my own people into the mix. I really try to use the community as one of the characters in my films. I’d shoot at my parents’ house, the scene with Emma Mae at the party was shot at my aunt’s house, there’s a scene in Brother Charles that we shot at the Compton Courthouse. My lawyer got me an appointment with the judge and he was saying that everyday he’d be sending a young black male to prison and it did his heart good to help a young black man trying to become a filmmaker. I would do whatever it took. I was definitely a guerrilla filmmaker. Instead of a dolly, I’d use a wheelchair, if I needed a helicopter shot, we’d just go to the top of a high rise, point the camera down and overdub a helicopter sound later. Whatever it took to accomplish what I needed to finish and make the best film I could make.

Where did you find Jerri Hayes who played Emma?

She was a theatre art major which was right next to the film school. I saw her in a play and was really impressed with her. I got a few actors for my films from that department.

You seemed to cast incredibly raw and authentic actors in your productions.

Hey sometimes I’d walk up to a person on the street if they had the right look. Malik Carter, who played Big Daddy, was just walking around on the UCLA campus and I asked him if he wanted to be an actor. I feel that if a person looks the part that I’m trying to portray, if I can relax the person and have them study the script to the point where it’s second nature to them so they’re not thinking about the lines, you’d be surprised at the performances you could get out of non-actors. I loved to put my family in my movies as well; it gives them a sense of immortality. It touches my heart every time I watch one of my films and get to see a family member in there.

Was Emma Mae directly inspired from your life?

The character Emma was based on my cousin Daisy Lee, who was from the country and she would come to visit us in Compton. Let me tell you when Daisy Lee was eleven years old she could kick a fifteen year old boy’s ass. If they messed with my brothers, they’d feel the wrath of Emma Mae. That taught me the power and warmth of female love. I wanted to show how I feel so blessed to be a filmmaker because you can use every art form in a film. You can use prose, paintings, poetry all the art that exists in the world can be depicted in a film. I didn’t get into film to get rich, I got into it so I could have a voice and show my community as a microcosm to the world and therefore it becomes a macrocosm.

How did you transition from Emma Mae to Penitentiary?

I shot two scenes from my earlier films at an old jail in Los Angeles called the Lincoln Heights Jail, most of the scenes you’d see on television or in the movies were shot there. Now most of the expense for making films was the location, so I realized I could write a story that all takes place in this prison. At the end of the day we wouldn’t have to pack up the equipment or anything and essentially incarcerate the film. We could literally keep the marks of a scene up overnight and come back in the morning and start right away with shooting.

There must have been some incredible stories from that production.

Well about three days before we wrapped the film I had completely run out of money. All the extras, cameramen, actors were still up for it, but insisted on at least getting fed while working, but I was completely broke. So, the guy who played Sweet Pea, Hi-Fi White, he said don’t worry about it, I’ll take care of it. I was unsure, but hey we needed to get back to work so I put my faith in him and sure enough Hi-Fi cooked the food at his house and brought it to the set and fed a hundred people for the last three days of shooting. And at the premiere I pulled Hi-Fi aside and asked him how he was able to get all that food for everyone? He went to all the extras, actors and crew and asked them if they had any food stamps they could donate and he gathered them up and bought and cooked enough food for everyone to share. That was the kind of comradery and the kind of pride we had going on.

Now do you purposely put in humor to lighten the tension and grit of your films?

Yeah, I’m a nut. You didn’t know that? Thomas Edison was a nut, until he invented the light bulb. Anybody coming up doing something different can be categorized as a nut, but I’m a proud nut. I even sued Hollywood you know. I sued the Directors Guild for failure to enforce the collective bargaining agreement. They have a clause in the agreement saying producers shall make distinct efforts to increase the employment of women and minority directors by a certain percentage each year. Now in the eighteen years before I filed my suit that percentage had actually decreased. I founded a group called the African American Steering Committee within the Directors Guild and educated myself thoroughly about the collective bargaining agreement. I eventually got before the board, filled with top of the line producers, studio heads and network presidents and asked them if they had any knowledge of this article stating these percentage increases and none of them had. Not one of them. How could they enforce a law that they had never heard of?

What came of your suit?

Well they thought of me as a tsetse fly, ignore him and he’ll go away, but the Directors Guild was angry at me. They set up a disciplinary hearing saying I’d done things against the Guild. It’s tough to take on Hollywood, because everyone is scared for their jobs. Especially nowadays when there’s about five companies running things, all you got to do is make what five phone calls to get somebody to never work in this town again. But I wasn’t afraid, I believed as a founder of the African American Steering Committee I was up for a fight. They were able to dismiss my suit on a technicality, but I went before the 9th circuit myself and won a reversal and got it back into court. I was all by myself against the biggest law firms in the country, and I lost on appeal. All the blacks you see on TV and in films right now are reaping the rewards directly from my lawsuit. One of my heroes is Curt Flood, who was a baseball player and he brought down the reserve clause which enabled players to be out of the control of the teams and become free agents. Now he didn’t get to profit from it, but others did. Similarly, I wasn’t fighting for myself; it was a class action suit for all minorities and women. I exposed the Achilles heel of Hollywood and they moved to change things, now I don’t get credit for it, but I look the mirror every day and feel pretty good about myself.

Do you think the lawsuit had a direct effect on your getting funds for new films?

Of course, even years ago after Penitentiary was the most successful independent film of 1979, both financially and critically, I couldn’t get any networks to show it! Not even cable, which has much stronger violence than Penitentiary would air it. That show Oz is a direct rip-off of my film by the way, even the warden was an actor in P2, and has very graphic violence and sex. My lawsuit was unpublicized, because the newspapers and Hollywood are both tied to their advertising and wouldn’t want to jeopardize their relationship over a nobody like me. It didn’t get any publicity even though everyone in Hollywood knew about it. I couldn’t get arrested in Hollywood for years. Now Turner Classic finally approached me, and I very grateful that they did, I’ve got a good relationship with them and they love my movies.

How has the digital age impacted your work?

I’m glad I’ve lived long enough to see the digitalization of the world. That really is a monumental step towards equality, I’ve never had a computer key refuse to respond to my finger. You can learn anything on a computer, even making an atom bomb. It’s kind of like rap music. Well, rap started in the closets and the bedrooms and the basements of America and the average Joe could make a record. They could make records that they liked, say the things that they thought should be said, they didn’t have to go to the man to get approval, and when I say the man, I’m not talking about the white man here, some of the worst things that have been done to me have been done by my fellow blacks. What happens is that the more successful a black man gets in this industry the less likely they are to stick their necks out for their fellow blacks. But now you get your digital camera and digital software and you are Warner. Every man has access to the means of production.

Tell us about your upcoming documentary, Hip-Hop Hope.

Well it’s about the hope that hip-hop engenders in the youth. I have a great affinity with hip-hop and some of their great artists. I had a long conversation with Snoop about how my films are his absolute favorites. It’s on my MySpace page if anyone wants to read about it. As for the documentary, I’m trying to get this interactive thing going. I’m putting the rushes on the computer and allowing people to have access and edit their own version of a hip-hop movie.

What are you up to now?

I’m working on a script for Penitentiary 4 and I’m hoping to independently finance it, but there is some studio interest. I’ve been through the wrath of Hollywood and I’m proud of what I did, someone had to say the emperor has no clothes. We’re planning to shoot in Los Angeles or possibly New Mexico. It’s going to be a gritty film much like P3. I am sixty five and this might be my last film and I sure want to go out with a bang.

Interesting interview, Dave. Got to run a lot more than I did in WaxPo 32. The joys of a blog. Fine work!

M

LikeLike

haha, yes. word limitations do suck. would’ve loved to see your interview in full but you nailed it given the limited space.thanks mark!

LikeLike

You kidding me? I don’t think you guys raelly understand the issue. Do you happen to know how Hollywood works? You can’t just crawl out of Cornell and hope that the road to becoming a great screenwriter is just going to meander its way to your doorstep. There are lots of good writers whose work never see the light of day sometimes until they are dead (knock on wood).What is he crying about? What racial discrimination? Can I sue Hollywood for not buying my script too?

LikeLike

And I was just wondering about that too!

LikeLike

Pbrt1E ifrsyytedukj

LikeLike

qM3lk9 fmwbyegbowzd

LikeLike

disse:ole1,vim te desjar um feliz 2013. Vc foi o primrieo blog que conheci, estava numa faze dificil de depresse3o e seu blog foi me animando, e comecei a ver todos so dias. Ente3o resolvi aprender a mexer melhor no pc e fazer um pra mim.te agradee7o muito vc nemimagina como me ajudou bjs a vc e o luquinha e o maride3o tambe9m. felicidades.

LikeLike

Dear Nerdtorious:

Great interview. I’m trying to recall exactly what time I did the interview with you and if

you have a nom de plume.

FFL, Jamaa Fanaka

LikeLike

fantastic interview. i’ve been reading this site for quite sometime and the content never ceases to surprise me.

LikeLike

I am awfully proud of this interview by Nerdtorious.com. “The truth shall set us free.”

F F L, Jamaa fanaka

LikeLike

Great n\interview Nerdtorious! F F L. Jamaa Fanaka

LikeLike

MPLDk7 zefwpfbsceme

LikeLike